The introduction and adoption of firearms in ancient India, a process that unfolded over centuries, significantly reshaped warfare, trade, and even social structures. While not always decisive in battles, the presence and increasing sophistication of cannons, harquebuses, and matchlocks had a profound impact on the military landscape of the subcontinent, particularly from the 15th century onwards. This article delves into the timeline, key players, and socio-economic implications of this technological shift.

The initial sparks of firearm usage can be traced back to the late 15th century with the campaigns of Sultan Mahmud Bigarh of Gujarat. However, these early deployments were isolated incidents. It was the arrival of the Portuguese in 1498 that acted as a crucial catalyst for the wider adoption and Integration of firearms into the Indian arsenal. The Portuguese, with their superior naval artillery, quickly established a dominant presence along the Indian coast, showcasing the immense potential of these New Weapons.

Babur, the founder of the Mughal Empire, further accelerated the spread of firearms in the North. His victory at the Battle of Panipat in 1526, achieved through the strategic deployment of field artillery, marked a turning point in Indian military history. While some historians argue that the artillery's impact on the battle's outcome was not overwhelmingly decisive, its novelty and effectiveness undoubtedly impressed the Lodi Sultans and their armies. Importantly, Babur’s artillery expertise came from Turkish sources, highlighting the diverse influences shaping the introduction of firearms in India. The Ottoman Empire, with its successful deployment of cannons and harquebuses against the Mamluks and Safavids, served as a testament to the disruptive power of this technology.

Following these early successes, the 16th century witnessed a significant increase in the use of firearms across the Indian subcontinent. The Battle of Raichur in 1520 provides a vivid example. Here, a small contingent of Portuguese mercenaries, armed with espingardas (early matchlocks), aided the Vijayanagara forces against the Adil Shahi Sultanate of Bijapur. This instance demonstrates not only the adoption of firearms but also the reliance on European expertise in their deployment. The Vijayanagara forces even captured a substantial cache of Bijapuri artillery, including hundreds of heavy cannons, signifying the growing recognition of their strategic importance.

While artillery was increasingly used in siege warfare, it's crucial to remember that traditional military elements like heavy cavalry, elephants, and infantry still held considerable sway. Early 16th-century warfare remained heavily reliant on these established strategies. However, as the century progressed, the increasing availability of European cannon-founders and weapons merchants steadily transformed the landscape. The Portuguese, in particular, played a significant role, not only introducing advanced weaponry but also offering their skills in cannon manufacturing and bombardment. Individuals like the Milanese artisans who transferred from Cochin to Calicut and the Goa-based trader Manuel Coutinho, who illegally sold harquebuses in Bengal, exemplified this trend.

Despite the widespread adoption, locally manufactured firearms were often of inferior quality compared to their European counterparts. This disparity fueled the demand for imported weapons, further contributing to the illegal trade and the dominance of European traders in the market. Nevertheless, whether locally produced or imported, the sheer quantity of firearms had reached substantial levels by the late 16th century.

The Battle of Talikota in 1565, a major clash between the Vijayanagara Empire and the Deccan Sultanates, showcased the scale of firearm deployment. Telugu sources claim the Vijayanagara army possessed a staggering 2300 large guns alongside numerous smaller ones. However, despite the claims of "great carnage," these weapons did not decisively impact the battle's outcome, which was ultimately determined by internal treachery and political maneuvering.

In the subsequent decades, European travelers and chroniclers consistently noted the prominent presence of firearms in the arsenals of South Indian rulers and fortified cities. Jesuit visitors to Senji and other fortified locations documented the abundance of "ordnance, powder and shot." Gasparo Balbi, a Venetian resident of Mylapur, provided vivid accounts of firearm usage in the region. Even further south, in places like Tanjavur, renowned for its artillery and firearm production, Jesuit sources described an impressive collection of cannons of varying sizes, even mentioning one large enough for a man to comfortably crouch inside.

By the early 17th century, the Tamil region and even the Telugu lands further north were well-supplied with firearms. Descriptions of engagements in Telugu forts, like the story of Basavana Buya defending Siddhavatam with a double-barreled jajayi, offer compelling evidence of their integration into local defense strategies. Dutch records from Pulicat and other factories along the Coromandel coast further confirm the widespread presence of firearms and the constant requests from local chiefs for the loan or sale of cannons. The Dutch, along with other European trading companies, played a key role in supplying these weapons, sometimes with unforeseen consequences.

The use of firearms also extended to unconventional tactics, such as ambushes. Dutch illustrations of campaigns in the Ramanathapuram region in the 1680s depict the use of firearms in conflicts between warring Marava clans. Jesuit accounts further reinforce the prominence of firearms in siege warfare and ambush tactics.

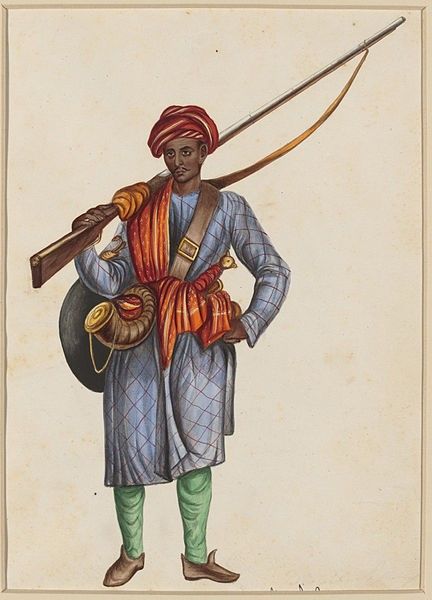

The adoption of firearms was also linked to the composition of armies. Mercenaries, particularly Portuguese parangis, were frequently employed for their expertise. However, their integration into existing military structures was not always seamless. The reliance on traditional warfare often limited the full potential of these foreign recruits.

Beyond their military applications, firearms began to exert a cultural influence. They found their way into literary works, appearing in hunting scenes, descriptions of war, and even erotic depictions, showcasing their impact on the popular imagination. Furthermore, firearms became associated with specific social groups, such as the Bedas and Boyas, who rose to prominence as chieftains during this period.

Literary sources like the anonymously authored Tanjaviiri andhra rajula caritra, which describes the fall of Tanjavur in 1673, emphasized the importance of firearms in warfare, reflecting the evolving attitudes of the warrior elite towards these weapons. The account highlights the extensive use of cannons and smaller firearms during the siege, contributing to the town's eventual surrender.

In conclusion, the spread of Firearms in ancient India was a complex and multifaceted process that transformed the military landscape and influenced broader aspects of society. From the initial introduction by the Portuguese to the widespread adoption by various kingdoms and social groups, firearms became an integral part of Indian warfare and culture. While their effectiveness varied depending on the context and the quality of the weapons, their presence undoubtedly left an indelible mark on the History of the Indian subcontinent.